Utilitarian VS Deontological Approaches to Human rights

When it comes to ethical decision-making, there are many different schools of thought. One approach is rights-based ethics, which focuses on the rights of individuals and groups. According to this perspective, everyone has certain rights that must be respected. For example, everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person. This means that no one should be killed, enslaved, or tortured. Additionally, everyone has the right to freedom of expression and freedom of religion. This means that people should be able to speak their minds and practice their religion without fear of retribution. Rights-based ethics is a powerful approach to moral decision-making, and it can help us create a fairer and more just world. But how do two major competing moral theories deal with human rights?

When it comes to ethical decision-making, there are two main schools of thought: consequentialism and deontology. Consequentialists believe that the morally right thing to do is the one that will produce the best outcome, while deontologists hold that there are certain actions that are intrinsically right or wrong, regardless of their consequences.

There are pros and cons to both approaches. Consequentialism is often criticized for being too cold and calculating, as it can lead to decisions that sacrifice individual rights for the greater good. However, proponents of consequentialism argue that this is a necessary evil in some cases, and that the ends always justify the means. Deontology, on the other hand, is sometimes criticized for being too inflexible, as it can lead to bad outcomes if rigorously followed. However, deontologists maintain that there are some things that we simply shouldn’t do, even if it would result in a net positive.

At the end of the day, it’s up to each individual to decide which approach they want to take. There’s no right or wrong answer, and both approaches have their own merits. Whichever one you choose, it’s useful to see what they look like when applied to human rights:

Consequentialism

Consequentialist ethics is the branch of ethics that evaluate the rightness or wrongness of an action based on its consequences. The main principle of consequentialism is that the end always justify the means – in other words, if the outcome of an action is good, then the action itself is good. This type of ethical system is often contrasted with deontological ethics, which judge the rightness or wrongness of an action based on its adherence to a set of rules or principles. The most famous advocates of consequentialism are probably utilitarians like John Stuart Mill, who argued that actions should be evaluated based on their ability to promote happiness. Other consequentialist theories have been put forward by philosophers like Peter Singer and Peter Unger. In general, consequentialist ethics tends to be more popular with theorists than with the general public – after all, it can be hard to sell the idea that “the end justifies the means.” Nevertheless, consequentialism remains a powerful and influential approach to ethical decision-making.

This approach has been used to justify a wide range of actions, from environmental conservation to lying in certain circumstances. When it comes to human rights, consequentialists typically argue that we should focus on promoting the greatest amount of happiness or well-being for the greatest number of people. This might mean sacrificing the rights of a few individuals if it would lead to a net increase in happiness. For instance, a government might justification taking away someone’s right to free speech if it would prevent a violent uprising. While this approach has its critics, many consequentialists believe that it offers the best way to protect human rights in the long run.

Deontology

Deontological ethics is the branch of ethics that focus on the rightness or wrongness of actions, regardless of the consequences. The word “deontology” comes from the Greek word for duty, and deontological ethical theories are sometimes also called duty-based ethical theories. Deontologists believe that there are certain things that we ought to do, regardless of whether they lead to good outcomes or not. For example, most people believe that it is always wrong to murder innocent people, even if doing so would lead to some greater good. Deontological ethical theories are usually contrasted with consequentialist ethical theories, which focus on the goodness or badness of consequences rather than on the rightness or wrongness of actions. Many modern ethicists, including some who are otherwise sympathetic to deontology, believe that deontological ethical theories have some serious problems. For one thing, it can be difficult to figure out what our duties are.

When looking at the issue of human rights, deontologists tend to focus on the intentions behind an action rather than the outcome. In other words, they believe that it is more important to act in a way that upholds human dignity and autonomy, even if this does not always lead to the best outcome. For example, a deontologist might argue that it is always wrong to torture someone, even if doing so would save lives. This is because torture violates the basic rights of the individual and is therefore intrinsically evil. Of course, this perspective does not always lead to easy answers, but it does provide a clear moral framework for addressing complex issues.

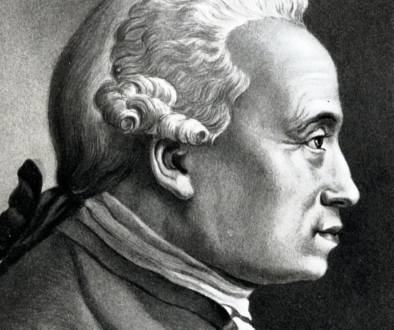

The deontological approach to human rights is based on the belief that everyone has certain inherent rights that must be respected. This approach was first articulated by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who argued that we have a duty to protect the rights of others even if it goes against our self-interest. Kant believed that human rights were universal and could not be taken away by any government or individual. The deontological approach has been influential in shaping modern human rights law, which guarantees everyone the right to life, liberty, and security of person. In recent years, the deontological approach has been criticised for its lack of flexibility, as it does not take into account the complexities of individual situations. However, it remains a powerful theory that continues to shape our understanding of human rights.