Do you have a moral obligation to help the world’s poor?

Despite my family not being Catholic at all, I went to a Catholic all-girls high school, because apparently when I was ten years old, I said that I wanted to go to a school without boys. I didn’t find the religious education, or the relatively conservative Christian values of the school to be much of a problem for most of my time there. Compared to the views of my Seventh Day Adventist (the Serbian half of my) family, my education felt rather progressive for the most part, with many members of my family objecting to the fact that we were taught about evolution in our biology classes, and we were told to not always take a literal interpretation of the bible, which again my family didn’t approve of. But there came a critical juncture in my Catholic education, which unbeknownst to me at the time, would change the trajectory of my life.

Being a Catholic school, it was compulsory to study religion in senior school, with two option available to us. ‘Religion And Ethics’ was similar to the religious education classes we’d taken in years eight to ten shaped by Catholicism, which didn’t count towards your overall score for university entry. Students who had no plans to attend university, or wanted a “bludge” subject chose RAE. ‘Study Of Religion’ was a more objective subject that explored how various religious traditions have influenced, and continue to influence, people’s lives, and our grade counted towards our overall score for university entry. I chose to do SOR, which ended up being a good thing, because only your top five subjects get used to calculate your university entry score, which meant my shockingly poor chemistry grades didn’t matter.

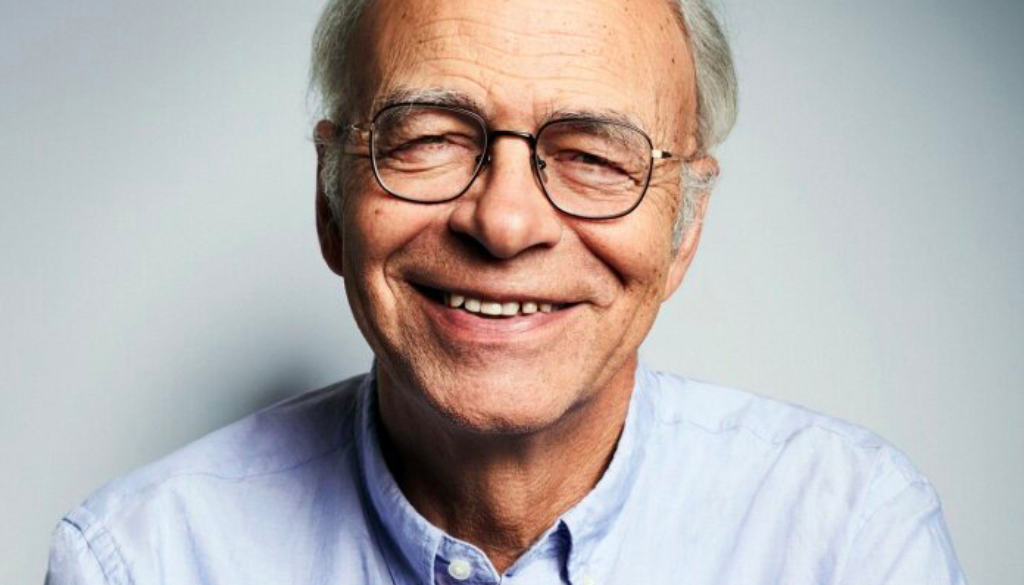

I’m not entirely sure what the unit of study was actually about, but in year 12 SOR we watched a documentary called “Peter Singer, a Dangerous Mind.” A 2003 documentary that even then, in 2013 seemed a little outdate, focused on the bioethics of Australian philosopher Peter Singer, who refuted traditional (read: Catholic) ethics on the questions of life and death. I’m assuming that the idea of showing us the documentary was to get us to oppose his ethics, given that they were in direct opposition to the core Christian value of the sanctity of life; the idea that human life, as an extension of God, is inherently sacred. This doesn’t appear to be too problematic at first, but when a human— which Catholics believe begins at conception— is considered to be inherently sacred, a woman’s right to an abortion is considered an immoral act.

One day in class we were presented with a quote from Peter Singer, taken way out of context, and asked to raise our hand if we agreed with his sentiment. The quote read: “An animal experiment cannot be justifiable unless it is so important that the use of a brain damaged human would be justifiable.” I raised my hand, along with one or two of my friends— the remainder of the class did not. When asked by the teacher to explain to my peers why I agreed, I explained my thoughts to the effect of “I completely agree with what he’s saying… if we think that if we use limited intelligence or cognitive abilities as the only moral justification for testing on animals, than that logic should extend to all animals, including humans. If we can’t justify doing it to a human, we can’t justify doing it to an animal.” Immediately, a girl in my class who came from a Catholic family chimed in with a story about her intellectually disabled uncle, who brings so much joy to her family, and how the thought of using him for experimentation upset and angered her. Did she not realise that she was only helping my argument more? “Exactly. And because you can’t justify doing something so cruel to your uncle, how could you justify doing it to any sentient being with the same ability to suffer or experience joy?” She didn’t want to listen to what I was saying. The teacher had succeeded, at least for one student, on further perpetuating this idea that human lives are more sacred than any other sentient being.

At this point in my life, I was already vegan, so the philosophy of Peter Singer— the guy who literally coined the term ‘animal liberation’ in his book of the same title in 1975, and who also coined the term speciesism to describe the idea that human lives are not inherently more valuable than non-human animals— resonated with me and was much more palatable than it may have been if I was not as receptive to the ethical idea that we should cause suffering for sentient beings. The topic of Peter Singer, and my in-class debate with that girl created a bit of a buzz around the school, for at lest a few days. Then one day, a friend of mine (shout-out to Kuei) gave me a copy of one of Peter Singers books. She knew that I was interested in a career in global development and that I was a fan of Singer, and she had received a copy of The Life You Can Save, Singer’s book that demonstrates that we have a moral obligation to help the world’s poorest. She was right. Not only did I love the book, but I ended up going on to major in philosophy at university, and even doing my honours in philosophy, with my honours thesis inspired largely by Singers book One World Now: the ethics of globalisation. When I think back to the fact that if I’d never received a copy of this book, I may not have even found myself working in the social change space (this is something I’ve mentioned in the HCN handbook, The Changemaker In You), it actually blows my mind.

In March 2022, I got to attend An Evening With Peter Singer, an event organised by Think Inc. where I was able to sit literally metres away from him, hear him talk, and even tell him that he inspired me to study philosophy (it was a truly cringe-worthy fangirl moment on my behalf).

In 2009, Peter Singer wrote the first edition of The Life You Can Save to demonstrate why we should care about and help those living in global extreme poverty, and how easy it is to improve and even save lives by giving effectively. Peter then founded a nonprofit organisation of the same name, The Life You Can Save, to advance the ideas in the book. Together, the book and organisation have helped raise millions of dollars for effective charities, supporting work protecting people from diseases, restoring sight, avoiding unwanted pregnancies, ensuring that children get the nutrients they need, and providing opportunities to not only survive but thrive.

SPOILER ALERT: the central argument of the book is as follows:

Premise 1 – Suffering from something and died due to lack of food are bad.

Premise 2 – If it is in your power to prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing anything as nearly as important, it is wrong not to do so.

Premise 3 – By donating to aid agencies, you can prevent suffering and death from the lack of food, shelter and medical care, without sacrificing anything nearly as important

Conclusion – if you do not donate to aid agencies, then you are doing something morally wrong. Whether or not a utilitarian approach to tackling global poverty is the best approach… that’s a post for another day! But the argument is one that is rather compelling, and one that catalysed my own journey as a changemaker and philosopher.

In the decade since the first book’s publication, dramatic progress has been made in reducing global extreme poverty. However, millions still live on less than $1.90 a day, and there is yet much to be done.

To address the continuing need, and to build on the success of the first edition, Singer acquired the book rights and updated the content to be current and even more relevant. With mission-aligned celebrity narrators and by giving away the audiobook and e-book for free (https://www.thelifeyoucansave.org.au/), the 10th-anniversary edition of The Life You Can Save aims to inform, inspire and empower as many people as possible to act now.